When the Epiglottis Does Not Function Properly, This Condition Can Cause

| Epiglottis | |

|---|---|

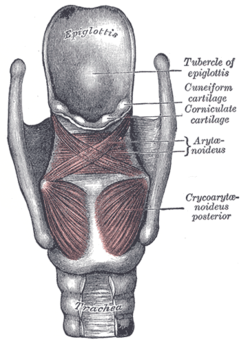

View of the larynx from behind. The epiglottis is the structure at the top of the image. | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | 4th pharyngeal arch[1] |

| Function | Prevent food from inbound the respiratory tract. |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Epiglottis |

| MeSH | D004825 |

| TA98 | A06.two.07.001 |

| TA2 | 3190 |

| FMA | 55130 |

| Anatomical terminology [edit on Wikidata] | |

The epiglottis is a leafage-shaped flap in the throat that prevents food and water from inbound the windpipe and the lungs. Information technology stays open during animate, assuasive air into the larynx. During swallowing, it closes to prevent aspiration of food into the lungs, forcing the swallowed liquids or food to proceed the esophagus toward the breadbasket instead. It is thus the valve that diverts passage to either the trachea or the esophagus.

The epiglottis is made of elastic cartilage covered with a mucous membrane, attached to the entrance of the larynx. It projects upwards and backwards behind the tongue and the hyoid bone.

The epiglottis may be inflamed in a status chosen epiglottitis, which is most commonly due to the vaccine-preventable bacteria Haemophilus influenzae. Dysfunction may cause the inhalation of food, called aspiration, which may lead to pneumonia or airway obstruction. The epiglottis is also an important landmark for intubation.

The epiglottis has been identified as early as Aristotle, and gets its proper noun from being in a higher place the glottis (epi- + glottis).

Structure [edit]

Location of the epiglottis

The epiglottis sits at the entrance of the larynx. Information technology is shaped similar a leaf of purslane and has a free upper part that rests behind the natural language, and a lower stalk (Latin: petiolus).[ii] The stem originates from the back surface of the thyroid cartilage, continued past a thyroepiglottic ligament. At the sides, the stalk is connected to the arytenoid cartilages at the walls of the larynx past folds.[ii]

The epiglottis originates at the archway of the larynx, and is attached to the hyoid bone. From in that location, it projects upwards and backwards behind the tongue.[3] The space between the epiglottis and the tongue is chosen the vallecula.[three]

Microanatomy [edit]

The epiglottis has ii surfaces; a forrad-facing anterior surface, and a posterior surface facing the larynx.[2] The forward-facing surface is covered with several layers of sparse cells (stratified squamous epithelium), and is not covered with keratin, the same surface every bit the back of the tongue.[2] The back surface is covered in a layer of column-shaped cells with cilia, similar to the residuum of the respiratory tract. It also has mucous-secreting goblet cells.[2] At that place is an intermediate zone between these surfaces that contains cells that transition in shape.[iv] The trunk of the epiglottis consists of rubberband cartilage.[two]

Development [edit]

The epiglottis arises from the fourth pharyngeal arch. It can be seen every bit a distinct structure later than the other cartilage of the pharynx, visible around the fifth month of development.[1] The position of the epiglottis likewise changes with ageing. In infants, information technology touches the soft palate, whereas in adults, its position is lower.[3]

Variation [edit]

A loftier-rising epiglottis is a normal anatomical variation, visible during an examination of the mouth. It does not cause any serious problem apart from possibly a balmy sensation of a foreign body in the pharynx. It is seen more oft in children than adults and does not need any medical or surgical intervention.[5] The forepart surface of the epiglottis is occasionally notched.[2]

Function [edit]

The epiglottis is ordinarily pointed upward during breathing with its underside functioning as part of the pharynx.[2] There are taste buds on the epiglottis.[6]

Swallowing [edit]

During swallowing, the epiglottis bends backwards, folding over the entrance to the trachea, and preventing food from going into it.[ii] The folding backwards is a complex movement the causes of which are not completely understood.[2] It is probable that during swallowing the hyoid bone and the larynx move upwards and forwards, which increases passive force per unit area from the back of the tongue; because the aryepiglottic muscles contract; considering of the passive weight of the food pushing down; and because of wrinkle of laryngeal and because of contraction of thyroarytenoid muscles.[2] The consequence of this is that during swallowing the bent epiglottis blocks off the trachea, preventing food from going into information technology; food instead travels downwards the esophagus, which is behind it.[three]

Speech sounds [edit]

In many languages, the epiglottis is not essential for producing sounds.[2] In some languages, the epiglottis is used to produce epiglottal consonant speech sounds, though this audio-blazon is rather rare.[seven]

Clinical significance [edit]

Inflammation [edit]

Inflammation of the epiglottis is known as epiglottitis. Epiglottitis is mainly acquired by Haemophilus influenzae. A person with epiglottitis may accept a fever, sore throat, difficulty swallowing, and difficulty breathing. For this reason, acute epiglottitis is considered a medical emergency, because of the take chances of obstacle of the pharynx. Epiglottitis is oft managed with antibiotics, inhaled aerosolised epinephrine to deed as a bronchodilator, and may require tracheal intubation or a tracheostomy if breathing is difficult.[8]

The incidence of epiglottitis has decreased significantly in countries where vaccination against Haemophilus influenzae is administered.[ix] [10]

Aspiration [edit]

When food or other objects travel downward the respiratory tract rather than down the esophagus to the stomach, this is called aspiration. This can lead to airway obstacle, inflammation of lung tissue, and aspiration pneumonia; and in the long term, atelectasis and bronchiectasis.[three] One reason aspiration tin occur is because of failure of the epiglottis to shut completely.[two] [3]

Should food or liquid enter the airway due to the epiglottis failing to shut properly, throat immigration[3] or the cough reflex may occur to protect the respiratory organisation and miscarry material from the airway.[xi] Where there is impairment in laryngeal vestibule sensation, silent aspiration (entry of textile to the airway that does not issue in a coughing reflex) may occur.[3] [12]

Other [edit]

The epiglottis and vallecula are important anatomical landmarks in intubation.[13] Abnormal positioning of the epiglottis is a rare cause of obstructive sleep apnoea.[14]

Other animals [edit]

The epiglottis is nowadays in mammals,[15] including land mammals and cetaceans,[xvi] also every bit a cartilaginous construction.[17] Like in humans, information technology functions to prevent entry of nutrient into the trachea during swallowing.[17] The position of the larynx is apartment in mice and other rodents, including rabbits.[iv] For this reason, because the epiglottis is located behind the soft palate in rabbits, they are obligate olfactory organ breathers,[eighteen] [19] as are mice and other rodents.[4] In rodents and mice, there is a unique pouch in front of the epiglottis, and the epiglottis is usually injured by inhaled substances, specially at the transition zone between the flattened and cuboidal epithelium.[20] [four] Information technology is also common to see taste buds on the epiglottis in these species.[4]

History [edit]

The epiglottis was noted past Aristotle,[15] although the epiglottis' office was first defined by Vesalius in 1543.[21] The give-and-take has Greek roots.[22] The epiglottis gets its name from being to a higher place (Aboriginal Greek: ἐπί, romanized: epi- ) the glottis (Ancient Greek: γλωττίς, romanized: glottis , lit.'tongue').[23]

Additional images [edit]

-

Cross-section of the larynx, with structures including the epiglottis labelled.

-

Cross-department of the larynx of a equus caballus. The epiglottis here is shown as '2'.

-

Structures of the larynx as viewed during laryngoscopy. The leafage-like epiglottis is shown as number '3'. Other structures: one=vocal folds, ii=vestibular fold, 3=epiglottis, 4=plica aryepiglottica, five=arytenoid cartilage, half-dozen=sinus piriformis, 7=dorsum of the tongue

Encounter likewise [edit]

- Epiglottal consonant

- Epiglotto-pharyngeal consonant

- Pharyngeal consonant

References [edit]

- ^ a b Schoenwolf, Gary C.; et al. (2009). ""Development of the Urogenital system"". Larsen's human embryology (fourth ed., Thoroughly rev. and updated. ed.). Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. p. 362. ISBN9780443068119.

- ^ a b c d e f 1000 h i j k fifty thousand Standring, Susan, ed. (2016). Grey's beefcake : the anatomical ground of clinical practice (41st ed.). Philadelphia. pp. 586–8. ISBN9780702052309. OCLC 920806541.

- ^ a b c d e f one thousand h Matsuo, Koichiro; Palmer, Jeffrey B. (Nov 2008). "Anatomy and Physiology of Feeding and Swallowing – Normal and Abnormal". Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America. 19 (iv): 691–707. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2008.06.001. ISSN 1047-9651. PMC2597750. PMID 18940636.

- ^ a b c d due east Harkema, Jack R.; Carey, Stephan A.; Wagner, James Grand.; Dintzis, Suzanne M.; Liggitt, Denny (2018), "Nose, Sinus, Throat, and Larynx", Comparative Anatomy and Histology, Elsevier, pp. 89–114, doi:ten.1016/b978-0-12-802900-8.00006-three, ISBN9780128029008

- ^ Petkar Northward, Georgalas C, Bhattacharyya A (2007). "High-rise epiglottis in children: should it crusade business organization?". J Am Board Fam Med. 20 (5): 495–6. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2007.05.060212. PMID 17823468.

- ^ Jowett, Adrian; Shrestha, Rajani (November 1998). "Mucosa and taste buds of the human epiglottis". Journal of Anatomy. 193 (4): 617–618. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.1998.19340617.10. PMC1467887. PMID 10029195.

- ^ Shahin, Kimary (2011), "Pharyngeals", The Blackwell Companion to Phonology, American Cancer Society, pp. i–24, doi:10.1002/9781444335262.wbctp0025, ISBN9781444335262

- ^ Nicki R. Colledge; Brian R. Walker; Stuart H. Ralston, eds. (2010). Davidson's principles and practice of medicine. illustrated past Robert Britton (21st ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. p. 681. ISBN978-0-7020-3084-0.

- ^ Reilly BK, Reddy SK, Verghese ST (April 2013). "Astute epiglottitis in the era of mail service-Haemophilus influenzae type B (HIB) vaccine". J Anesth. 27 (two): 316–7. doi:10.1007/s00540-012-1500-9. PMID 23076559. S2CID 33540359.

- ^ Hermansen MN, Schmidt JH, Krug AH, Larsen Chiliad, Kristensen S (April 2014). "Low incidence of children with acute epiglottis after introduction of vaccination". Dan Med J. 61 (4): A4788. PMID 24814584.

- ^ Widdicombe, J. (1 July 2006). "Cough: what's in a name?". European Respiratory Journal. 28 (1): 10–15. doi:10.1183/09031936.06.00096905. PMID 16816346.

- ^ Ramsey, Deborah; Smithard, David; Kalra, Lalit (13 December 2005). "Silent Aspiration: What Practise We Know?". Dysphagia. twenty (3): 218–225. doi:10.1007/s00455-005-0018-9. PMID 16362510. S2CID 24880995.

- ^ Peitzman, Andrew B.; Rhodes, Michael; Schwab, C. William (2008). The Trauma Transmission: Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 86. ISBN9780781762755.

- ^ Catalfumo, Frank J.; Golz, Avishay; Westerman, Due south. Thomas; Gilbert, Liane Chiliad.; Joachims, Henry Z.; Goldenberg, David (2018). "The epiglottis and obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome". The Journal of Laryngology & Otology. 112 (10): 940–943. doi:10.1017/S0022215100142136. ISSN 0022-2151. PMID 10211216.

- ^ a b Leroi, Armand Marie (2014-08-28). The Lagoon: How Aristotle Invented Science. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 145. ISBN9781408836217.

- ^ Perrin, William F.; Würsig, Bernd; Thewissen, J. K. M. (2009-02-26). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press. p. 225. ISBN9780080919935.

- ^ a b Colville, Thomas P.; Bassert, Joanna Thou. (2008). Clinical Anatomy and Physiology for Veterinary Technicians. Mosby Elsevier. p. 251. ISBN9780323046855.

- ^ Suckow, Mark A.; Stevens, Karla A.; Wilson, Ronald P. (2012-01-23). The Laboratory Rabbit, Republic of guinea Pig, Hamster, and Other Rodents. Academic Printing. p. 209. ISBN9780123809209.

- ^ Johnson-Delaney, Cathy A.; Orosz, Susan E. (2011). "Rabbit Respiratory System: Clinical Anatomy, Physiology and Disease". Veterinary Clinics of North America: Exotic Animal Practise. 14 (ii): 257–266. doi:10.1016/j.cvex.2011.03.002. PMID 21601814.

- ^ Treuting, Piper 1000.; Dintzis, Suzanne M.; Montine, Kathleen Southward. (2017-08-29). Comparative Anatomy and Histology: A Mouse, Rat, and Human being Atlas. Academic Printing. pp. 109–110. ISBN9780128029190.

- ^ Bug in Anatomy, Physiology, Metabolism, Morphology, and Man Biology: 2011 Edition. ScholarlyEditions. 2012-01-09. p. 202. ISBN9781464964770.

- ^ Lydiatt DD, Bucher GS (March 2010). "The historical Latin and etymology of selected anatomical terms of the larynx". Clin Anat. 23 (ii): 131–44. doi:10.1002/ca.20912. PMID 20069644. S2CID 10234119.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "epiglottis | Origin and meaning of epiglottis by Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com . Retrieved 26 Oct 2019.

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Epiglottis. |

- lesson11 at The Anatomy Lesson past Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (larynxsagsect)

- Where is the Epiglottis? at Written report Sciences

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epiglottis

0 Response to "When the Epiglottis Does Not Function Properly, This Condition Can Cause"

Post a Comment